For twenty five years, Jonathon Ellison of Kingscroft has worked as a landscape architect, helping to change the shape the world both locally and on the international level. Specializing in sustainable land use planning, Ellison has worked on projects all over the planet, ranging from houses to holy sites.

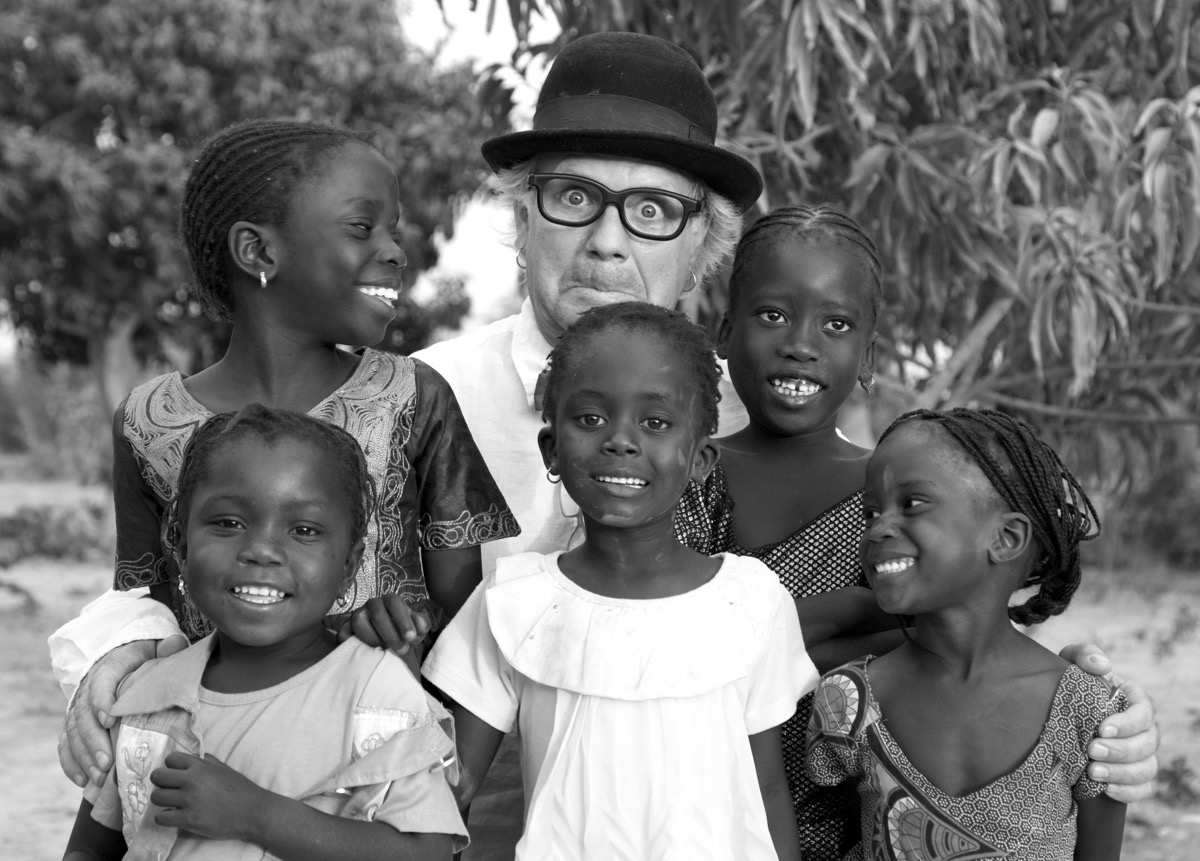

For the last three years, he has also been working as a clown in Africa.

“I’ve always been the class clown and the family clown,” Ellison told The Record. “It’s very second nature to me to clown at the dinner table to reduce tension.”

Though humour has been with him throughout his entire life, the landscape architect explained that it was in 2013, while working in Senegal on Africa’s western coast, that the clown came out to serve a new purpose in his life.

“During my travelling I would witness these landscapes of women working that I wanted to find out a bit more about,” Ellison said. “I made the very typical western mistake of feeling that I could take photos without permission, and the women became very upset (…) The next day I showed up as a clown to say I was sorry and to offered to work to make that up. They found that hilarious.”

Ellison explained that as the clown he turns his own cultural and historical background on its head, laughing at himself, western privilege, whiteness, and male authority in order to help break down the walls between himself and the women in three different villages he has been working with. Once those barriers come down, the landscape architect turned documentary filmmaker said that he has only one job.

“This project is about listening,” Ellison said. “I don’t go in trying to fix anything or change anything.”

The clown, in his whiteface and bizarre clothing, takes on whatever task the women are doing in the community and follows their direction. In a situation where white people have a legacy of being the masters and women are subservient to men, Ellison said that initial reactions to his actions range from bafflement to uproarious laughter. Once the laughter comes, though, what follows after is a whole different take on humanity.

“They’re saying things that are very profound,” Ellison said. “I hear about the mistakes that Europeans made in Africa. I hear grandmothers talk of how, over their whole childhood, when they saw a white they would run and hide. I hear women talk about how we still control the majority of their economy. I hear them say that if 1,000 women ran every country then there would be no more war.”

Though Ellison has been working directly with the three communities in Senegal for the last three years, he said that the work draws on an interest he has played with in his comedy work for a lot longer.

“I’ve always been interested in the stupidity of the male brain,” the clown said. “I believe the common thread in all of what the world is suffering with right now is the male brain. It’s not the only thing, but I think that’s the biggest common thread.”

That understanding of the world, he continued, is what automatically makes hearing women’s perspectives on things fascinating for him.

“(This project) is not just about making a movie, it’s about really hearing what potentially thousands of women have to say, and opening up that discussion,” he shared. “In many instances if I wasn’t dressed up as a silly clown there’s no way I could do what I’m doing.”

While Ellison gave credit to the confrontational style of documentary filmmakers like Michael Moore, he underlined the fact that he believes humour, and particularly humour that makes fun of the self rather than others, allows the conversation to go further.

“The fool in Shakespeare is the only one who can speak the truth, everyone else gets their heads cut off,” the clown said. “What I’ve found with humour is that it opens doors that wouldn’t be there if the humour wasn’t present. The further I push the humour envelop, the further I can go with more difficult questions, but if I went in as a serious white man with a serious white agenda, they wouldn’t respond to that.”

Ellison emphasized that his work is not silliness for silliness’ sake, but rather an organized self-mockery meant to open up deeper issues with society.

“I am part of the male brain and the white westerner, I can’t separate myself from that,” he explained “That’s really important; I don’t go in saying I’m an exception to the rule. I am part of that. It’s a really important part of the whole process that I mock that.”

Ellison’s film project is ongoing, and he spoke of the possibility of other developments like a book in the future, but when asked about his objectives for the work, the clown and landscape architect turned back to his expertise in sustainable planning and said that from what he hears, the women he works with have something to show the world about how the west approaches international development and aid.

“We have to be careful to not fall into the mistake of saying this works here so it will work there,” Ellison said, explaining that he has seen plenty of examples of abandoned projects from large scale charities in his travels. “Listening is a big part of what we have to do differently.”

Ellison said that in his experience the women, who traditionally have very little voice in their communities, know very well what their communities need. By building the trust and taking the time to listen and learn from these women, he continued, the opportunity exists to help people build up their own communities from within rather than trying to impose outside solutions.

“These women need to be at the forefront of their own decision making,” Ellison said.

Though he underlined the fact that he is not clowning in order to impact communities directly, Ellison also noted with interest the effect his presence seems to have had on younger boys.

“When I do “women’s work” and the little boys see it and they see their moms really happy, there’s something happening there because they often come out and they start to mimic the clown,” Ellison said. “I’m not telling them to do this, but they’re mimicking what I’m doing. I think we need a better understanding of why those little boys imitate the clown, and break cultural barriers. I’m hugely inspired when I see little boys do that.”